From dirt to dinner

Erica Yetman

Share Article

When searching for the perfect apple, tossing aside the bruised and beaten, you could be adding to the ever-growing pile of less-than-perfect (but perfectly edible) foods filling our landfills.

Lester’s Farm in St. John’s is a landmark for people who want fresh local produce, but its beginnings were humble.

Susan Lester remembers a story her mother Mary loved to share of her walking through the fields back when the farm was growing only “staple” vegetables such as potatoes, carrots, cabbage and turnip. Back then, Susan says, it was all about which farm had the best price.

“Sometimes you’d plant everything and they (distributors) wouldn’t take it all, so she’d be walking through the fields and see perfect heads of romaine lettuce just go bad,” said Susan. “That's when she decided to pull a table to the side of the road.”

Mary Lester thought it was important to sell directly to the customers. As a result, the customers could meet the farmers and know where their food was coming from.

We try to promote that as we go, buying fresh and knowing who’s growing your food.

— Susan Lester

Seventy years ago, living off the land to provide for your family was standard for many Newfoundlanders. Often, it was the only means of providing - you grew what you could, and often bartered for the rest.

Wasting food was not an option.

Somewhere along the way things changed. Cupboards became stocked with cans of SpaghettiOs and boxes of Kraft Dinner. Ships filled with produce from across the world docked in our harbours and filled store shelves.

Currently, according to Stats Canada, Newfoundland produces just 10 per cent of its own food. We account for less than one per cent of all farms in the country, and Canada’s 2016 Food Report Card says we buy so much food that more than 40 per cent of us admit to throwing away a shopping bag full of food - or more - a week.

40 per cent of Newfoundlanders admit to throwing away a shopping bag full of food or more a week.

- Canada's 2016 Food Report Card

Farm to table

Unlike many farms in Newfoundland, Lester’s sells directly to consumers. This practices allows Lester’s to adjust their prices based on how much product they have, says Susan, and how much they expect to sell.

“We’re were harvesting as fresh as possible. We don’t have too much wastage because we’re only harvesting what we need.”

On a busy Saturday, Lester’s can go through as many as 20 trays of romaine lettuce, says Susan. So in preparation for the day, field workers will generally have five or ten extra trays ready.

We’re were harvesting as fresh as possible. We don’t have too much wastage, because we’re only harvesting what we need.

— Susan Lester

A rainy or windy season can affect the growing process, and Susan says it’s possible you could end up with much more wastage than normal - though it varies.

“We’ve had a lot of trial and error over the past 24 years in business. We’re after learning a lot from our mistakes for sure,” said Lester. “We try to improve every year.”

Every January, the Lesters will sit down and go through the numbers for the previous years to determine if they need to increase or decrease prices or production. Things like carrots cost the same price to grow as something like artichokes. But the demand for carrots is higher than the demand for artichoke, says Susan, so they would plant more carrots to factor in the demand and profitability.

While it’s not an exact science, Susan says the farm makes it a priority to eliminate waste as much as possible.

“Sometimes it works,” said Susan, with a chuckle.

Homesteading and happy

Ten years ago Lisa and Steve McBride were living the city life in the hustle of downtown Vancouver. They both worked at an international coffee chain and were living average lives. It was time for a change. They packed up, moved to St. John's, bought two goats and started a small garden in their backyard.

“We try to be mostly self-reliant for pretty much everything we can do, our own vegetables, our maple syrup, and we keep bees for our own honey,” said McBride. “It allows for a lot less wastage.

Today, they live in ‘cabin country’ as McBride calls it - three kilometres down an unpaved road on the Southern Shore - living off the land as much as possible.

“If you take it and break it down into little components yourself, you do what you can,” said McBride.

“There's definitely arrangements like that out there to divert waste (that way),” said Carlson. “It’s another thing that can help.”

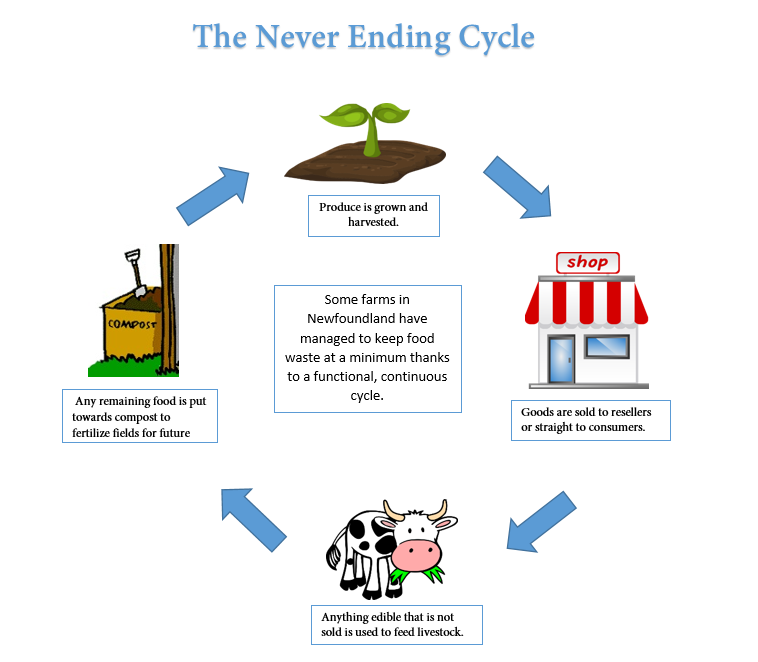

The cycle is something that can be found on many farms in the province, and selling directly to consumers is a great way to cut down on the amount of food wastage, says Carlson.

“That’s sort of your top three: sell what you can for human consumption; whatever you can’t do that way next would be try to line it up as animal feed; and then compost because you’re still getting something of value out of it, “ said Carlson. “I would say that’s very typical of how it’s dealt with.”

A cracked egg

When selling to wholesalers, up to 20 per cent of produce could be considered ‘unsellable’, said Carlson, and it could be for any number of reasons. However, farmers who are selling directly to consumers could waste as little as five per cent of their goods.

“Say in the egg industry, if they have a cracked egg there’s only so much that can be done with that,” said Carlson. “Or your potatoes that don’t look real good a wholesaler might say no to, but a processor looking to make french fries might say that’s fine.”

However, according to the Commission for Environmental Cooperation, the food production and farming industry in Canada is responsible for four million of the 13 million tons of food waste being brought to our landfills each year.

You have a moral obligation to do something once you realize how much is going on.

—Lisa McBride

“It’s much better what’s done here (NL) versus what's done other places has been my read of it,” said Carlson. “Where there’s so much direct- to-consumer being done, a lot of it is just cut out pretty well immediately.”

While the McBride’s didn’t start out intending to dedicate themselves to homesteading, once they fell down the ‘rabbit hole’, McBride says they couldn’t stop.

“At some point you realize that you can’t effectually make large change without making individual change first,” said McBride. “Now in the modern day when we have the knowledge to change we should as individuals try too. For us it was something as simple as growing our own food so we’re relying less on the grocery store.”

“There really isn’t any going back,” said McBride. “You have a moral obligation to do something once you realize how much is going on.”

Be the first to comment