Tara Nanayakkara is a visually impaired author with three books to her credit and more on the way.

Arlette Lazarenko

Kicker

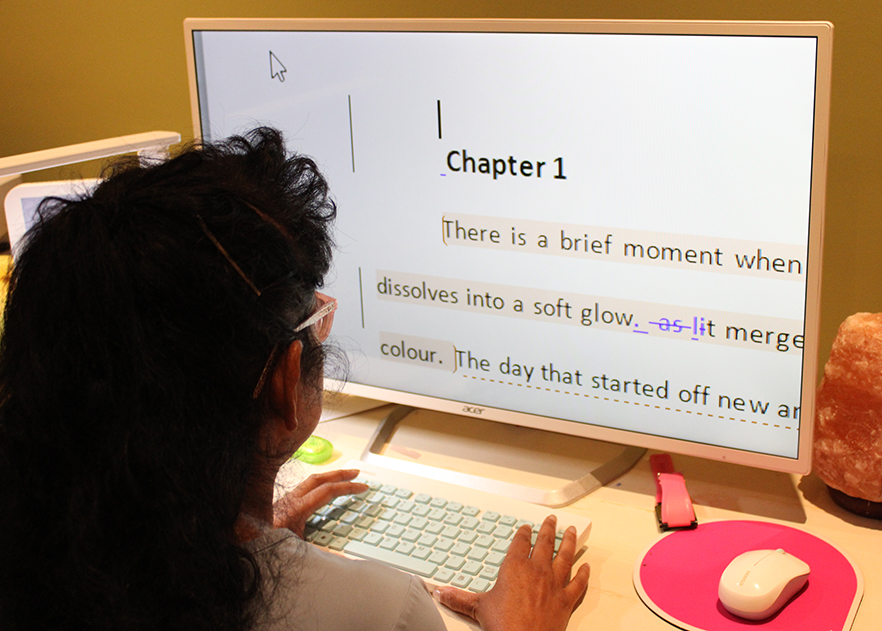

In a lit corner of her basement, a woman carefully types as her face almost touches the keyboard.

Tara Nanayakkara is writing her next book.

Nanayakkara, 59, is visually impaired. She was born with a condition called congenital cataracts. Her eyes are cloudy. She has about 10 per cent of vision in her left eye and about five per cent in her right.

“I was born supposedly only seeing shadows,” Nanayakkara said.

That’s what she recalls her mother telling her as a child.

She wrote her first novel when she was 19.

Born in Sri Lanka, Nanayakkara moved to St. John’s with her family when she was three.

Growing up, she says she felt misunderstood.

She went to a regular school in the province. The only school for the blind in the early 70s was in Halifax. However, her mother, a school teacher herself, wanted her close to home so she made a deal with the local school that she would help Nanayakkara catch up.

“The teachers branded me lazy, unmotivated, not working to my potential. These were the labels back then when they didn’t know what they know now about living with a disability,” Nanayakkara said.

She says the school system failed her.

“I remember the guidance counsellor telling my mother when I was in Grade 10 that I was arrogant. That people try to help me, but I brush them off, don’t wave at them in the hallway and ignore them.”

Newfoundland and Labrador lacks a school for the blind and visually impaired. Instead, schools have access to an itinerant, or travelling, teacher who usually comes to a school at the start of the year and guides visually impaired children. Once they have been shown the available accessibility tools, the teacher leaves.

According to the Canadian Institute for the Blind, 1.5 million people in this country are either blind or partially blind.

Nanayakkara’s first book, To Wish Upon a Rainbow, was published in 1989. She wrote it on a typewriter in her parents’ house under a bright lamp, pressing tiny keys. Today, she still uses a lamp, but she writes on a specialized keyboard.

There are transcription programs that she could dictate to, but she doesn’t use them.

“I can’t formulate my thoughts this way,” said Nanayakkara. “If I had to verbalize them, the ideas wouldn’t come. I would be stilted.”

There is, however, one tool that helps Nanayakkara write – music.

“I am inspired by music. Without music, I couldn’t write. I see the scenes like a movie with the music. I change it based on the scene I’m writing.”

Music is a central part of her life. She learned to play the piano not by large, printed sheets of music but by hearing her mother play a note and then mimicking it. She says she always had perfect pitch.

Often when one sense is impaired, other senses improve. However, she doesn’t credit her perfect pitch to her impaired vision.

“There are lots of able-bodied, perfectly sighted people who have these skills. It’s just that I happen to have it, and I happen to have a disability, but I don’t have one because of the other. I don’t think so, anyway.”

At school, she says she was “a fish swimming with whales.” She had to learn and do things in an unconventional way, which put her at odds with the teachers and the system.

A support network, she says, was critical to her success.

“I met this lady who was the assistant superintendent of the school board who believed in me in a way that others didn’t,” said Nanayakkara. “She told me I had writing talent. When I was 18, she invited me to speak at a national book week convention for junior high students.”

Elizabeth Mayo, who is visually impaired herself, was another one of the author’s biggest supporters. She is the hosting committee chairwoman for the Canadian Council of the Blind.

“The CCB is a self-help advocacy group where we support one another,” said Mayo.

They host events such as talent shows, bowling, swimming and dances.

The council also supports the visually impaired by providing guidance for accessibility tools that work with phones and computers.

Through the council, Mayo and Nanayakkara met and began a friendship that has lasted for more than two decades.

“I would encourage her because I know it was difficult for her with her vision, and she wasn’t sure if she would get published,” Mayo said.

Nanayakkara, a mother of two, has published two more books and is writing her memoir as a visually impaired minority.

“You try your best to believe in yourself,” Nanayakkara said. “But if you find that hard, find the people who will believe in you and support you. Because I don’t think you can do it all by yourself. No one can.”

Be the first to comment