The Newfoundland and Labrador government is trying collaborative team clinics as a possible solution to a family doctor shortage. The results have been mixed so far.

Arlette Lazarenko

Kicker

Rafaela Silva landed in St. John’s from Brazil six years ago. Around that time, the pain started.

She couldn’t explain why her stomach felt like it was burning or her back hurt to the point of waking her up at four in the morning. She didn’t have a doctor.

Luckily, she had access to the Memorial University’s wellness centre through her husband Murilo, who was doing his master’s degree in engineering. The counsellors suggested over-the-counter painkillers. She religiously took the medication, but the pain prevailed.

She wanted a diagnosis, a doctor, someone who would investigate deeper what was going on and track the pain that stubbornly persisted in her life.

Silva is one in 125,000 people in Newfoundland and Labrador who don’t have a family doctor, according to a poll commissioned by the Newfoundland and Labrador Medical Association.

A new approach

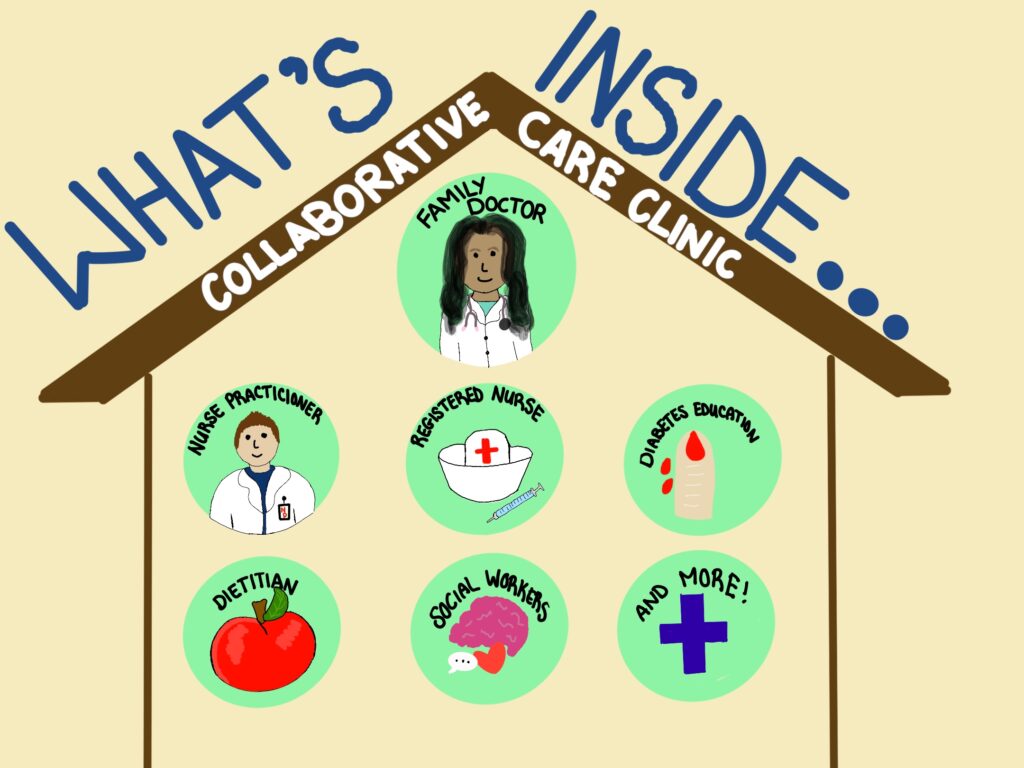

Patients who want care through a collaborative team clinic can register with Patient Connect NL.

Eastern Health staff then assign patients to a collaborative team clinic by looking at their medical information and location and prioritizing them according to their health needs, says Melissa Coish, regional director of primary health care and chronic disease.

One couple prioritized for access to a collaborative team clinic were Anna and Humberto Piccoli, Silva’s close friends, who are also from Brazil.

When the Piccolis arrived in St. John’s a year ago, Anna was 12 weeks pregnant.

Through the help of the local Brazilian community, they found another couple who recommended a maternity doctor.

When Anna was in the last stages of her pregnancy, the maternity doctor advised that they join a collaborative team clinic. They filled out a simple form online, and a month later, they were attached to the clinic on Mundy Pond Road.

Humberto, a master’s degree student in musicology at MUN, holds his two-month-old daughter Isabel and rocks her gently.

“When Isabel was born, the nurse would come and check on her in our house. Other times, we would email her about a health concern and get a reply the same day.”

Anna, who was a history teacher back in Brazil, says she experienced a bout of depression a few weeks before Isabel was born.

Depression isn’t new to Anna; she meets with a counsellor regularly online. A nurse at the Mundy Pond Road clinic who heard how Anna was feeling directed her to one of the clinic’s counsellors – demonstrating the collaborative element of the clinic.

The collaborative team clinics have been new to the province’s health-care system but not to the medical students at Memorial University.

Dr. Vernon Curran is a professor of medical education and chairman of the governing council for collaborative health professional education (CCHPE). The centre has since 2005 brought together students from various health-care fields to learn about each profession’s role and how to work collaboratively.

“There is evidence demonstrating collaborative care is much better in patient outcomes,” Curran said. “For example, in the case of chronic disease, we know diabetes is managed much better if there is a collaborative care approach.”

According to Curran, who has published articles on the efficiency of collaborative care, patients are more satisfied because they feel their providers spoke with each other and made a well-rounded plan that focused on each provider’s strengths.

This model also reflects a new generation of medical professionals who want more life and work balance. In this approach, when providers work together, they share the workload.

According to Coish, Eastern Health slowly evolved to the current model of collaborative teams in the past two decades.

“Change takes time, and I believe we’ve been working towards this place (collaborative team clinics),” Coish said. “We’ve done smaller versions of teams. We have been evolving over the years and have been picking up speed.”

The small steps to a collaborative approach included putting nurses and social workers in family practice and integrating electronic medical records so information could flow better between medical professionals. The next logical step was putting different professionals under the same roof.

Coish says it was time to make a significant change because pressures put on the health-care system by limited resources and the departure of medical workers. The transition to a collaborative team approach was to help not only patients without family doctors but also to retain medical professionals.

“It feels like it’s brand new, but really we’ve been doing it for some time,” said Coish.

Family doctors leave private practice to join clinics

After three years of living with the pain, Silva found a family physician on the Find a Doctor NL website, where people can check for doctors who are taking new patients.

The treatment her doctor recommended to her was more painkillers. But Silva was wary.

She knew a bit more than the average person about health care because she graduated from nursing school back in Brazil. However, she says she hasn’t practised nursing in Newfoundland because her education didn’t reach provincial standards. So, instead, she worked as a personal care attendant until she quit a year ago in 2021.

But even with medical knowledge, Silva couldn’t diagnose herself. So she begged her doctor for a CT scan of her back to further investigate her pain, which was becoming unbearable.

“My back hurt to the point I went blind for how intense it was,” Silva says. “I can’t keep relying on medication for the rest of my life.”

“I work with the pain, go to the grocery store with pain, cook with pain, watch TV with pain, do everything with pain until I can’t handle it anymore and take medication.”

Silva says that because she has a background in nursing, she knew enough to be careful about how much medication she could take and what alternative could help alleviate the pain. “I don’t want to think about someone who does something irreversible to themselves because they were desperate to get rid of the pain.”

Finally, Silva’s doctor agreed she would schedule a CT scan and an endoscopy, but didn’t have a date set. That was a year ago.

Then recently, Silva got news she couldn’t believe – her doctor was leaving.

The doctor will join one of the collaborative team clinics and leave her patients behind, Silva included. With her shoulders slumped and a weak smile, Silva says doesn’t know what to do anymore.

Besides the physical pain, the doctor was treating Silva’s anxiety and depression as soon as she learned about them. Now, she won’t have a doctor to rely on.

According to Coish, Eastern Health separates family doctors who join the clinics from their previous patients because the structure of the clinics is designed to connect patients based on their proximity to the clinics.

The attachment to a clinic is based on a patient’s needs and location.

Through a community needs assessment, Eastern Health gathers information about an area’s age population, the rate of chronic diseases, and social determinants of health. With that information, it builds a team to treat the people in the area better.

Coish says the clinic’s vision is to give access to health care closer to people’s homes.

“We appreciate that it created some angst among patients who had (a family doctor) because that continuity in that relationship is important, and we don’t want to downplay that,” Coish said.

“But we did have to create a system that had a little bit of flexibility but also some structure so we could have a streamline process to get patients cared for.”

Adam Reid, the inter-professional education coordinator of the CCHPE, confirms that setting up collaborative care clinics does have an unintentional side-effect. Silva is not the only one who has lost a doctor to a collaborative team clinic.

“People who had family doctors and now do not is contrary to the objective of having those teams set up in the first place,” Reid said. “So that’s why we see, hopefully, a temporary increase in people without family doctors.”

“Economically, it’s better because you have the right person providing the right care instead of one provider trying to fill as many roles as possible,” Reid said. “So, for example, a social worker who provides counselling instead of a physician who provides it and is beyond their scope of practice.”

Reid predicts that once the collaborative care clinics have had more time to establish themselves, more people will have better care in the long term.

A PhD candidate, Reid researches community health and policies that support it. Although he doesn’t have specific data regarding Eastern Health clinics, Reid said general research suggests patient satisfaction is better in collaborative settings.

In an ideal situation, Reid says, the clinics work like an oiled machine where all the parts – the various health-care providers – work together to ensure patients receive the best treatment.

However, no model is perfect, and Reid says one problem that clinic teams will face will be deciding what the best treatment looks like.

“There will be a period where workers will come together to resolve their differences of opinion and conflict, but the benefit as they grow is they become more competent and efficient in the long run.”

Reid says the public’s expectation of needing to see a doctor will need to change. Once a patient is attached to a team of professionals, one of the members would know the details of that person’s personal health history and provide the treatment.

Although Rafaela Silva is tired, she is hopeful. Now that she knows about the collaborative team clinics, she says she will consider applying to the growing waiting list while she checks online daily for a doctor.

Her hope is fueled by other news: She has been accepted into the nursing school at MUN. She loves the profession so much that she doesn’t mind starting all over again.

“I love helping people, and I want to make a change. I know I’m only one person, and this problem isn’t new, but I know how it feels to be in pain and desperate. If I can help, I will.”

Related Stories

Nova Scotia and New Brunswick have more experience with collaborative team clinics

Kicker Video Report: Health hubs save patients from long wait times in emergency

Podcast: An in-depth look at health hubs

Be the first to comment