While the collaborative health-care model is new to Newfoundland and Labrador, other provinces such as Nova Scotia and New Brunswick have been using the system for years.

Sara-Dani Strickland

Kicker

The collaborative health-care model has gathered praise from officials, but it might not be the quick fix in addressing the shortage of family doctors in Atlantic Canada.

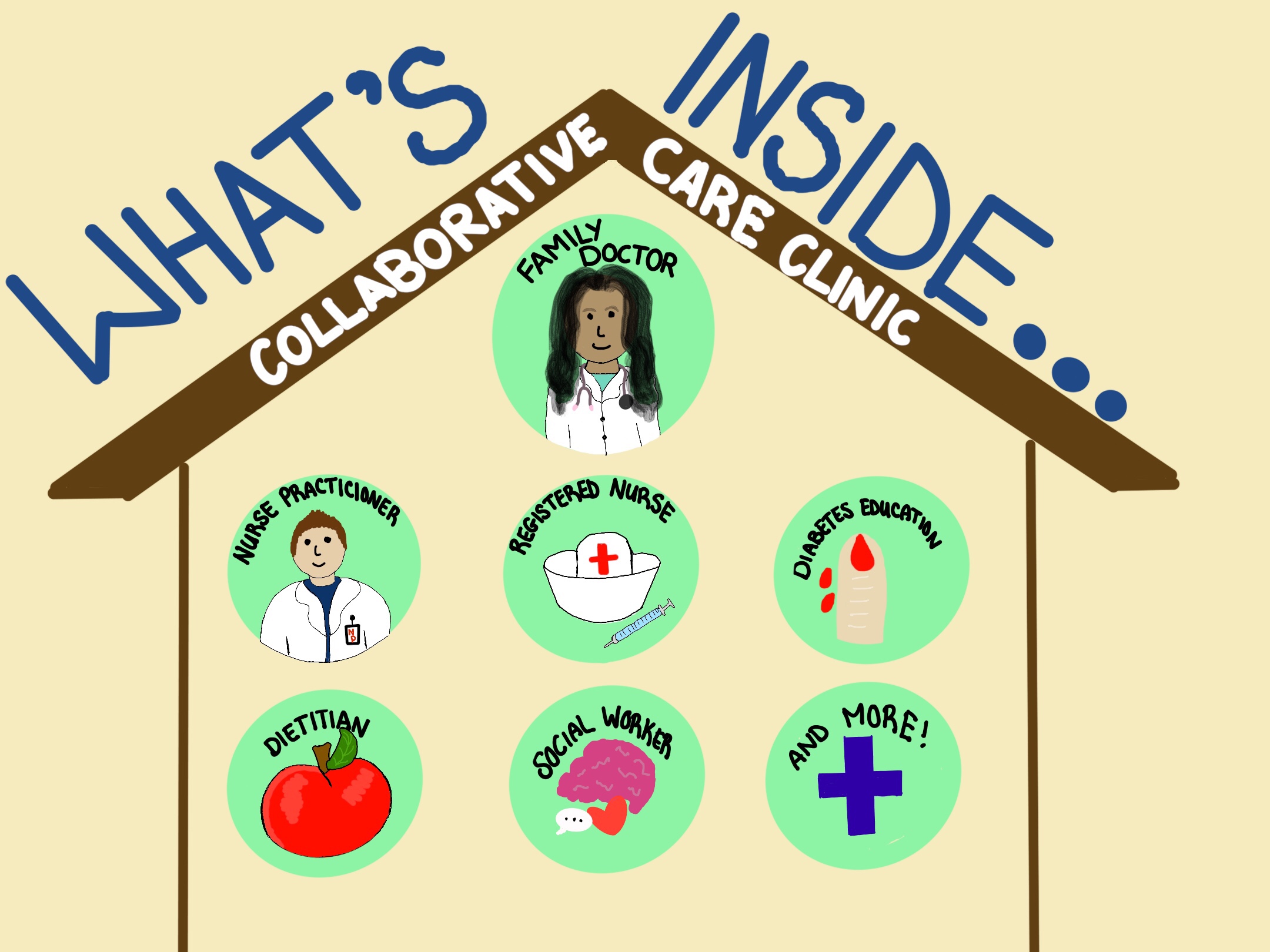

Collaborative team clinics are designed to have a variety of healthcare providers under one roof. The providers to share the workload, allowing the clinic to accept a higher volume of patients.

The model is meant to be convenient for patients as they can receive a variety of healthcare services all under one roof.

Nova Scotia first introduced the model in 2008. Since then, more than 90 collaborative team clinics have opened across that province.

The model has gotten increasingly popular, but one official says there is more work involved beyond staffing a clinic.

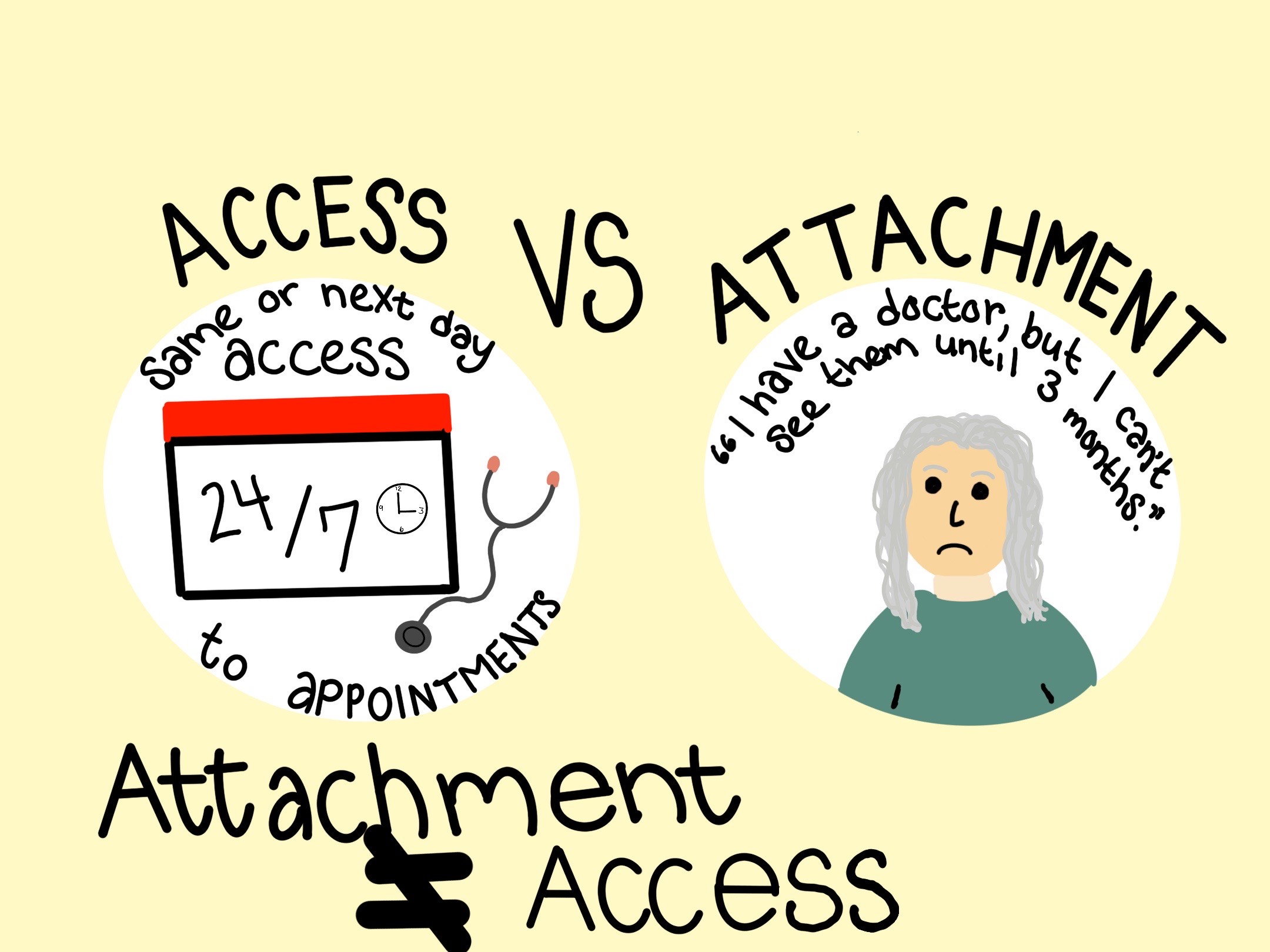

There are a variety of approaches to collaborative care. One approach requires that health-care providers distinguish between access and attachment.

Stephanie Wood, manager of primary health care for Nova Scotia Health Services, says attachment to a doctor in the system doesn’t mean that you have sufficient access to a doctor.

“Attachment is essentially just saying, ‘I have a family provider,’” said Wood. “Access is a whole different thing. It’s not really great access if it takes you three months to get in to see your provider.”

Collaborative team clinics are aimed at providing someone with both attachment and access. The goal is to attach someone to a clinic and allow them to have immediate access to staff in that clinic, depending on their concern.

Change can be difficult

The collaborative team health-care model was introduced to New Brunswick in 2017.

According to the CEO of the New Brunswick Medical Society, Anthony Knight, the province kept a close watch on other provinces who had been using the model.

“The evidence really led us there in terms of the success from other provinces and even around the world,” said Knight. “We needed to leverage the skills of family physicians by adding other health-care providers.”

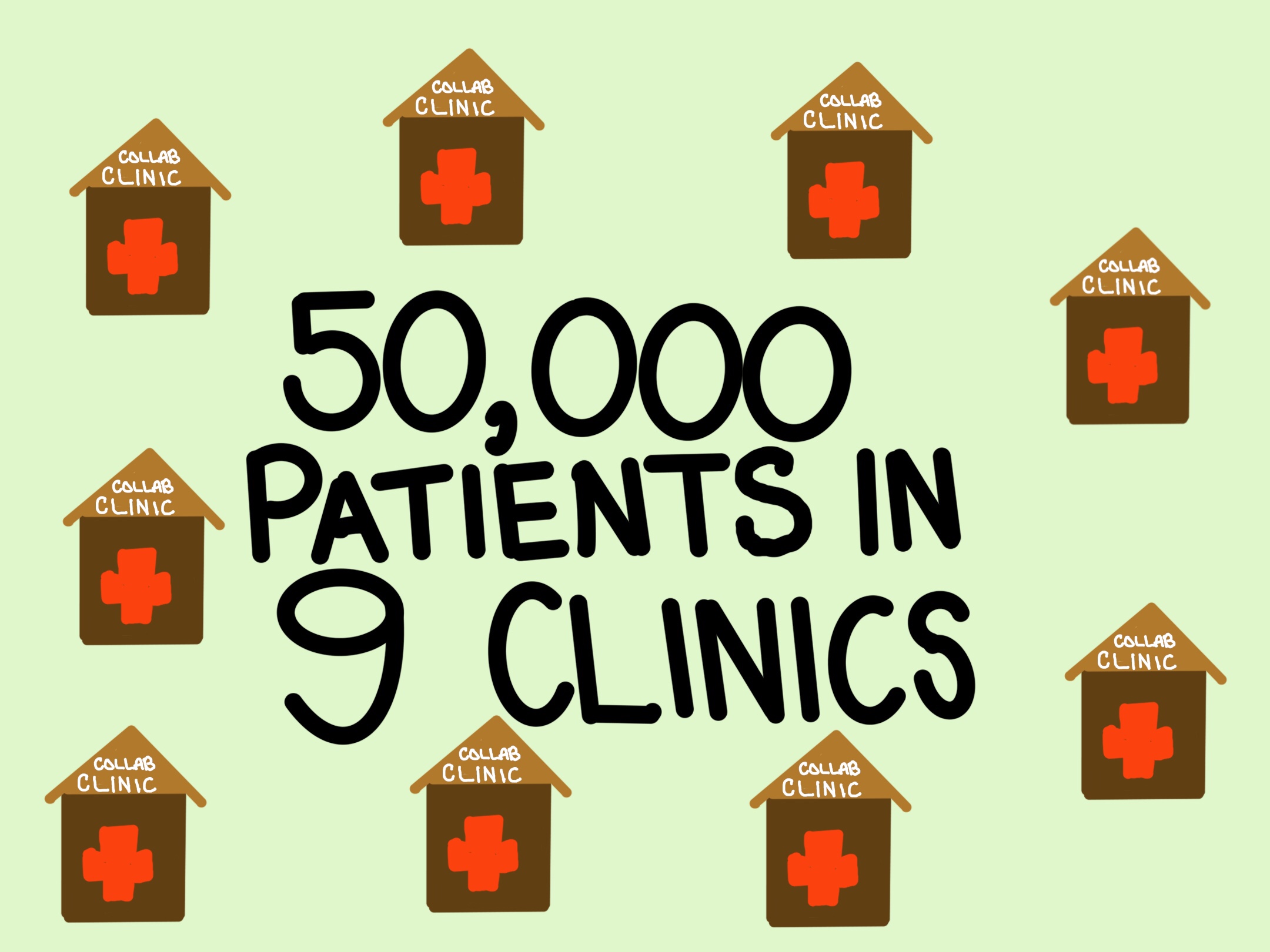

Since New Brunswick decided to implement the model, nine collaborative clinics have opened there.

Since those clinics opened, 50,000 people have obtained primary-care providers.

While some might think providing collaborative health care is as easy as opening the floodgates for anyone needing a provider, Wood says planning is more important than even officials may realize.

For Nova Scotia, finding medical staff to work in collaborative team clinics has been an issue. With the amount of retirement outweighing the amount of recruitment, the province is forced to turn to the United Kingdom to recruit doctors who are already trained to work in a collaborative environment.

Many established physicians, Knight says, aren’t quick to buy into the new health-care approach.

“Encouraging folks to change is always difficult,” said Knight. “But we continue to see physicians join the program.”

Doctors hesitant over payment plans

Wood says she doesn’t believe there are any disadvantages to the idea of collaborative care clinics.

In a perfect world, being able to see multiple health professionals in a one-stop-shop setting would be convenient for both providers and patients.

The issue, says Wood, is that the system is not set up to support the initiative to its full potential.

Along with retirement and recruitment issues, convincing existing providers to get on board with the idea has been a challenge.

“You need to have physicians buy in to have this work,” said Wood. “This can’t be something we impose on them. It doesn’t matter what great idea we have; they need to believe in it too.”

In both Nova Scotia and New Brunswick, some collaborative team clinics allow doctors to bill fees for service while other clinics pay them salaries.

Wood says many physicians say all collaborative team clinics should be based on a payment plan in which a doctor would receive a lump sum salary rather than a fee-for-service payment plan.

If doctors were to share the workload with others, Wood suggested, they would not benefit from being paid based on the volume of services they provide in their own clinics.

Knight says disagreement over payment methods is also an issue in attempting to staff the clinics operating in New Brunswick. A fee-for-service payment plan could mean that established physicians would make less money because they’re sharing their workload.

Orphan patients

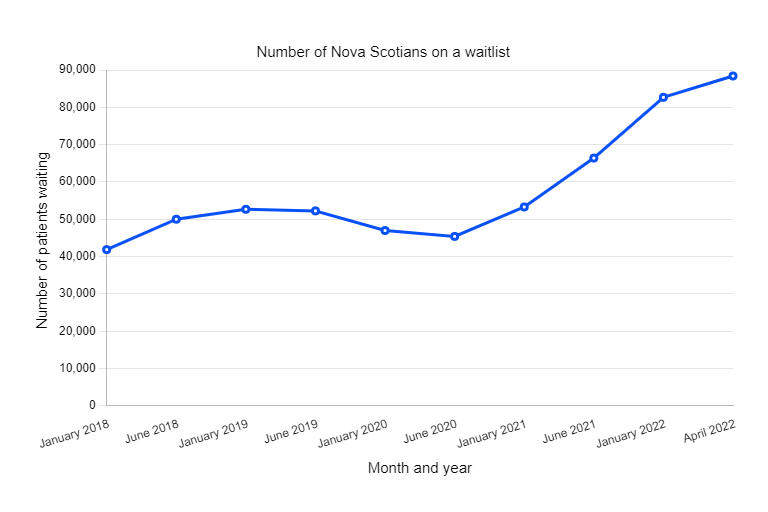

Low recruitment paired with a growing population has led to more people being left without a primary-care provider.

As of April 1, more than 88,000 Nova Scotians were on a waiting list for a family doctor.

That number, says Wood, might not be accurate as patients must identify themselves as in need of a provider.

“The reality is, we probably don’t have everyone (in need) on it (the list) and we probably have people who are on there who just don’t like their provider and are looking to get another one,” said Wood.

An issue with the collaborative care model is that many people think they can put themselves on a waitlist, then pick and choose a provider of their choice.

Take it or leave it, Wood advises people looking for primary care.

“I think in an ideal world, there would be enough capacity so that they could choose the provider that makes sense for them,” said Wood. “Right now it’s not a dating service. We don’t get to find the perfect match.”

A balanced approach:

Wood and Knight say the collaborative model of primary care will create a balanced work-life relationship for health-care professionals.

By having multiple health-care providers working to full scope, less responsibility falls on a single provider.

By working together, says Wood, there is a decreased risk of burnout.

“The last thing we want to do is recruit and have people work for two years and then take off because they just can’t handle it,” said Wood.

In New Brunswick, Knight says there is less pressure on doctors in emergency rooms since the collaborative care clinics have opened.

Since introducing the collaborative care model in New Brunswick, Knight says work-life balance for those in health care has improved.

“I think both physicians and non-physician staff have felt benefits from the program, – like ensuring that there is a member of the team to cover for patients when others are on holiday or sick leave.”

Health benefits

Along with decreased wait times for those seeking care in the emergency, Knight says the overall health of New Brunswick residents has improved.

According to Knight, access to diabetes educators through the collaborative clinics has been extremely beneficial to those living with diabetes.

“We’re seeing an increased access to information helping (diabetics) manage their (blood sugar) levels,” said Knight.

Advice for Newfoundland and Labrador

Adapting a modern approach like the collaborative team clinics brings a new outlook to the future of health-care.

“It’s an exciting journey,” said Wood.

As exciting as the collaborative care might be, Wood says communication between officials, physicians and patients in Newfoundland and Labrador is important if the clinics are to work.

“Build in quality and evaluation so you can understand quickly where things may need to change,” Wood advises. “Reach out to us. Reach out to other (provinces) who have done this before. Learn from the things we wish we’d done differently.”

Wood believes the collaboration of multiple people should take place not only in the clinics but throughout the health-care system.

“We can only be stronger when we work together, but we have to be willing to work together.”

Related Stories

Province takes collaborative approach to family doctor shortage

Check Up Podcast: Dr. Cindy Fontaine on collaborative team clinics

Video: Health hubs save patients without family doctors from long wait times in emergency

Check Up Podcast: Nicole Peyton of Killick Health Services on health hubs

Be the first to comment