The 1989 scandal haunts lawyers and journalists 30 years later

Ashley Sheppard,

Kicker News

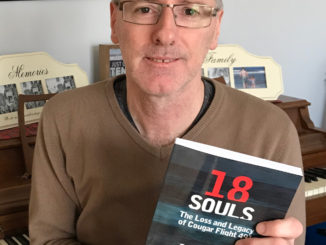

Geoff Meeker remembers it like it was yesterday. He recalls the tremble in Shane Earle’s voice over the telephone line at the Sunday Express. He sounded afraid, yet determined.

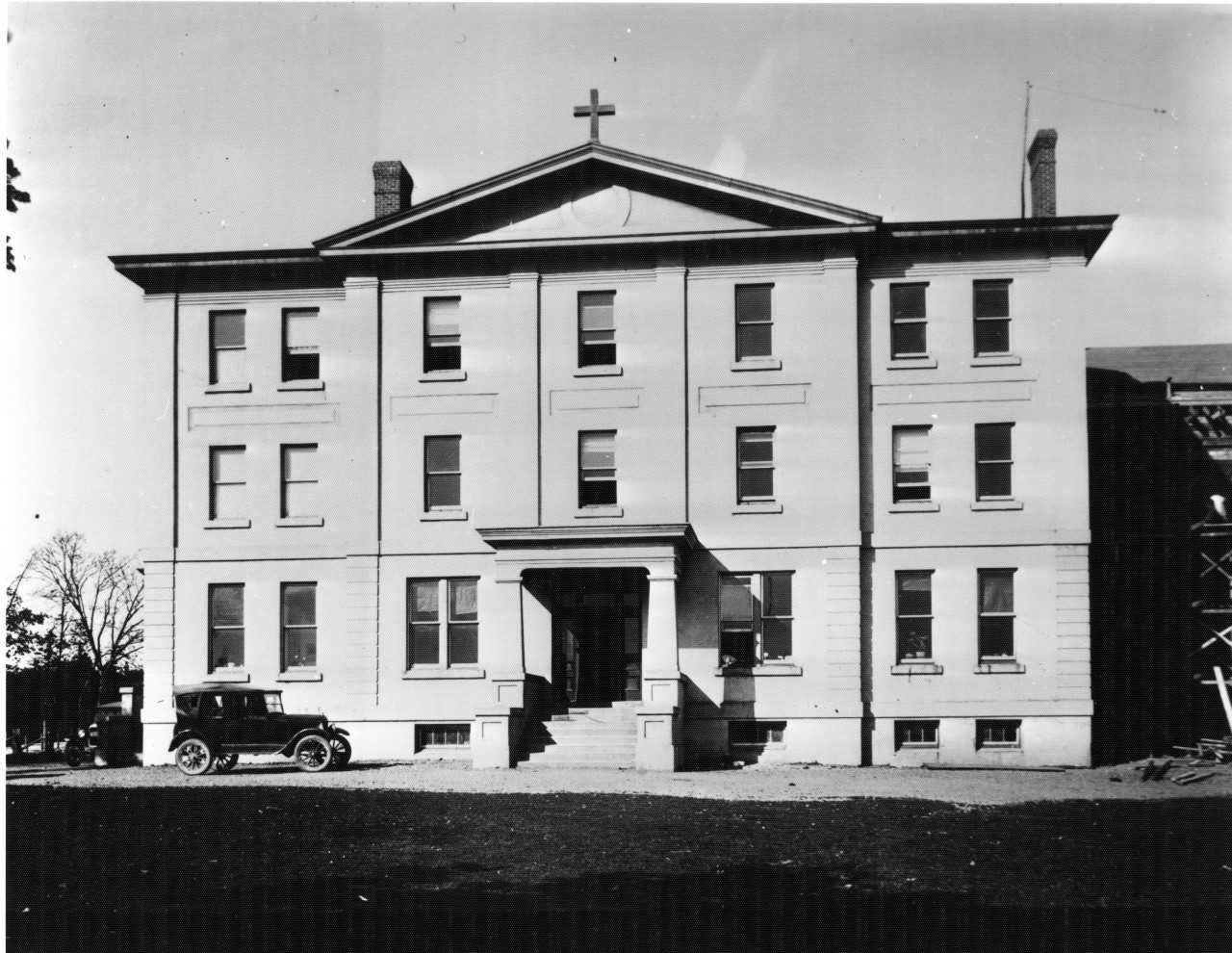

It’s been 30 years since Meeker was on the other end of that dreaded phone call. Thirty years since decades of abuse within the Mount Cashel Orphanage were brought to light.

“The stories were harrowing and horrible,” said Meeker. “Those kids went through hell and back.”

In 1987, Meeker became a reporter for the Sunday Express, an independent weekly in St. John’s that closed its doors in 1991.

Upon receiving the allegations that the Congregation of Irish Christian Brothers were physically and sexually abusing the children that were under their care, Meeker and other journalists at the paper were quick to get the story to the public. The impact was huge – and the province’s reaction quickly led to a public inquiry within weeks of the stories and interviews being released.

Some journalists will devote their lives to transparency and truth. But there is often a price to pay. The reporters who spoke to victims and listened to gut-wrenching testimony at court are are still tormented by the stories etched in their memory.

“As a journalist, that’s something that sticks to you,” said Meeker. “All the bad news comes to you because it’s your job to report it.”

As a Telegram reporter covering the scandal, Glenn Whiffen says not once did he feel deterred from journalism. He still works at the publication to this day.

“I wanted to expose what was happening. I wanted to tell the public,” said Whiffen. “A couple of times I got wrapped on the knuckles for putting too much details in my stories, but I was so determined to, as much as I was allowed to, tell those stories – that I wouldn’t miss a thing. I was there every day, every trial.”

But Whiffen says there are some things that will always haunt him – the grimy details of court testimonies being some of the worst. He still talks to a lot of those men, the men who were lucky enough to lead lives with some normalcy after the abuse. He says many ended up struggling with addiction, mental illness and torn-apart families. Others have even killed themselves.

“Then they were adults out in society,” said Whiffen. “They had to try to deal with the damage that was done to them that no one ever helped them with. Then they had to go and try to navigate their lives and some of them took wrong turns.”

What made this story even more daunting for some reporters was the secrecy within the media.

Initial allegations of abuse arose in 1975, but for the most part, people were silent. Despite members of the congregation admitting to sexual wrongdoing, the investigation was curtailed and two members of the congregation were placed in treatment centres outside the province. They were then transferred to other Christian Brother institutions in Canada. Not much media attention came about again until it blew open 1989.

“Even the Telegram at the time and other publishers didn’t want their reporters digging too deep into it,” said Whiffen. “That was troublesome for me as a reporter – to learn that. When I was covering it, there was no holding back.”

Whiffen says the church’s having as much authority as it did in those times was in large part why they had been getting away with the abuse for so many years.

People looked up to the Christian Brothers. They applauded them for being good Samaritans, saints and even workers of God.

“The church had a lot of power in those days,” said Whiffen. “Nobody wanted to tarnish 100 years of the Christian Brothers’ work in Newfoundland and Labrador.”

Secondary trauma

Geoff Budden says it was a miscarriage of justice.

He was a young lawyer when he started on the case. He represented only a few of the victims because the more senior lawyers took on the bulk of the cases.

That changed, however, when earlier residents of the orphanage came forward about the abuse they experienced in the 1950’s under the supervision of the American Christian Brothers. Suddenly, Budden was immersed in a lawsuit that’s still ongoing to this day.

“When I started the case, it didn’t enter my mind that I’d still be doing it in my mid-50s.”

Budden has worked in close quarters with the victims of Mount Cashel and intends to continue until there are adequate consequences for the actions of the church.

It’s been hard, he admits. He says it is similar to what anyone who worked on the case, in whatever way, might feel.

“Secondary trauma is the trauma you feel or experience when you see suffering,” said Budden. “It’s obviously not at the same level of actually experiencing the suffering, but it is harmful and disturbing. So, it’s not something that’s unique to me or unique to law. It’s a widespread thing, and all kinds of people you meet every day come home from work having seen or heard some terrible things.”

Budden saw faith dissipate from not only the victims but from the province as a whole. He says it was a turning point in the way Newfoundland values religion as an authority. The Catholic Church no longer has the power it once did.

“My personal belief is that the clergy scandals, Mount Cashel in particular, was a big reason why all of that changed,” said Budden. “As a society, though we are more traditional and more observant than many, we’re nothing like what we were 30 years ago.”

In 1992, the Irish Christian Brothers formally apologized to the former residents of Mount Cashel. The government also acknowledged its responsibility in the matter and paid a settlement to some victims.

The Christian Brothers announced the closure of the orphanage in November 1989. When the last resident was formally relocated the following year, they permanently closed the facility. In 1992, it was demolished.

Though the Mount Cashel trial with the Irish Christian Brothers is officially closed, Budden is still fighting for the victims of Mount Cashel who never received closure. The case with the American Christian Brothers is still ongoing.

Shortly after victims came forward in 1989, many men followed suit and came forward about the abuse in the orphanage that took place years before, in the 50’s. The civil trial was filed in 1999; the victims against the archdiocese.

In 2018, the court ruled the Roman Catholic Episcopal Corporation not liable for the abuse that took place in the in the 1950s.

Budden says his team recently filed an appeal and will be back in the courtroom in three weeks.

No matter how many years pass, the people deeply involved in the uncovering of the Mount Cashel scandal may never escape the memories burrowed in the corners of their minds.

“I used to come home and be affected by it in the night time,” said Whiffen. “I had trouble processing it and sleeping. But just imagine what it was like to be a victim.”

I lived there the pain never leaves my mind.

So very sorry to hear of your pain. Sending good wishes for future peace of mind.