Mexican journalists work in a world of threats and murder.

Arlette Lazarenko

Kicker

Geovanna Herrera was on the way home from the newsroom one evening when she noticed two men walking behind her. She suspected they were following her, so she picked up her pace. Then they started to run after her. She wasn’t fast enough, and they grabbed her. One hand on her throat, the other holding a gun pointed at her head.

“They told me to stop poking around, then they said the names of my family, my sister, my brother, his daughter, my kids and where they live,” said Herrera. “They took my phone, my wallet and my recorder where I had all the interviews and evidence. Then, they pushed me to the ground and started to kick me.”

In the first month of 2022, four journalists in Mexico were killed. Journalists that sought to uncover corruption, organized crime and social injustice such as the latest victim Roberto Toledo, have been slaughtered in the streets.

A few days before she was attacked, Herrera investigated a case in Mexico City. A group of people wanted to take over the shop space of a 92-year-old man in a central market. He held the spot for his entire life and worked hard to keep it. Because he was frail and had no family, he was helpless against them.

Herrera heard his story and collected evidence.

It wasn’t the first time Herrera’s life was in danger. She is 31 years old and had worked in journalism since she was 17. While covering political and social matters, she experienced death threats on daily basis, but that didn’t stop her.

“I don’t know why, but I never felt fear,” she said. “When you see a person that needs help, you help them. That is how we are as people. So, when I saw that man, alone and defenseless, I felt a moral obligation to him, not just to my job,” she said.

The attack was the worst she ever experienced because it was no longer a threat, but a physical assault.

“They are not doing it for the pay, because the pay is low, it’s because they have a passion for it, and I admire them for that because I don’t know anybody that could pay what your life is worth.”

– Adrian Sierra

“I was covered in bruises, bleeding, four of my teeth were broken,” Herrera said. “That was when I decided to quit. I wasn’t responsible just for myself back then, as a single mother I had two young children that were dependent on me. I knew I couldn’t put my life at risk anymore, who would take care of them?”

Today, four years after the incident, Herrera is working in the communication department of the secretary of public education in Mexico City. She is in contact with journalists every day. Her children are six and seven years old. She waits for the day they are old enough to care for themselves so she can return to journalism and fight the good fight.

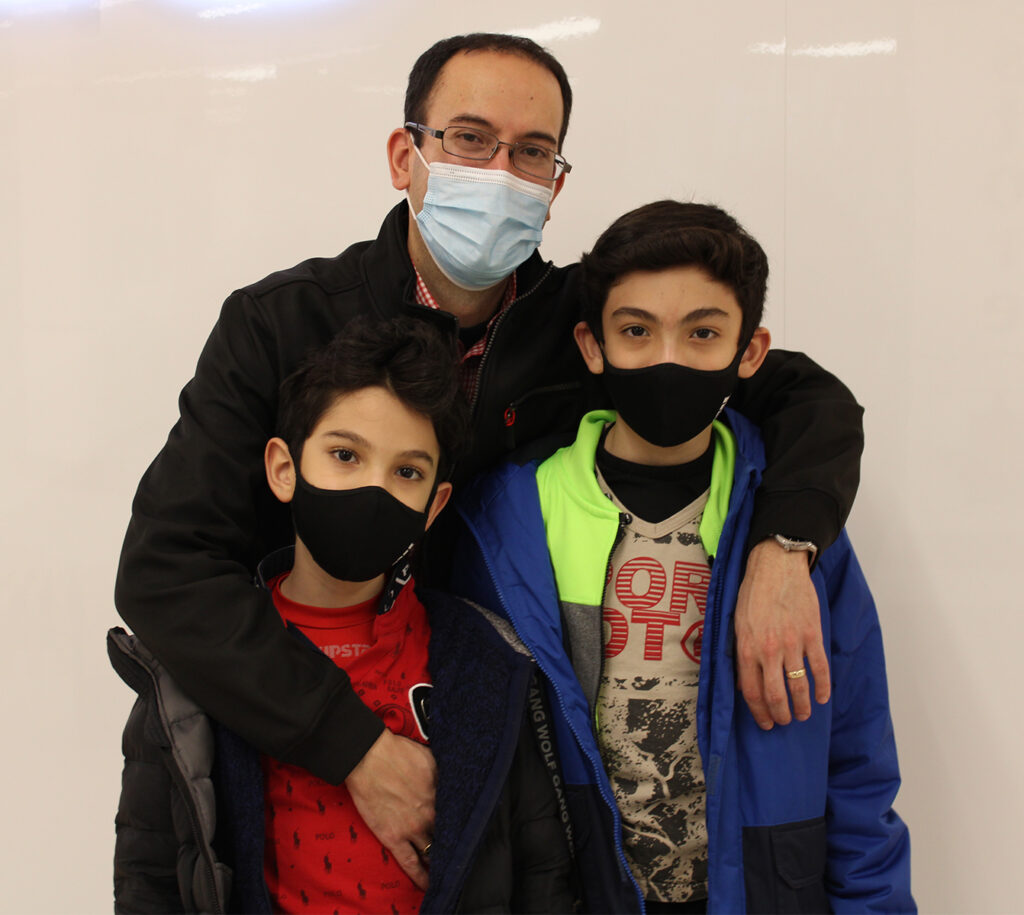

Adrian Sierra was a sports journalist in Mexico City and Herrera’s journalism teacher. He, his wife and two children moved to St. John’s last year.

“When I compare the journalists covering hard news to myself covering sports, I was doing kids play,” he said.

“I would come back after covering a game sharing my excitement, and they would say how they witnessed a gang fight and saw people get killed. For them, that is just another day at the job.”

In Mexico there is no insurance for journalists, Sierra said. If they die on the job, their families are left with nothing.

“They are not doing it for the pay, because the pay is low, it’s because they have a passion for it, and I admire them for that because I don’t know anybody that could pay what your life is worth,” said Sierra.

When asked if he is afraid to open a newspaper and see a name he recognizes, Sierra let out a heavy sigh and slowly shook his head.

“Oh. That would be a terrible day,” he said.

“Don’t get me wrong, the life of a journalist isn’t worth more than anyone else, but when someone kills a journalist, they also kill a voice that represents many.”

Be the first to comment