MUN’s Tahir Husain believes batteries made from vanadium are the wave of the future, but some local challenges remain.

Nick Travis

Kicker

A vanadium redox flow battery, or a VRFB, is what some people are calling the future of energy storage.

According to Vanitec.org, the batteries are scalable, not prone to starting on fire, don’t degrade easily and are entirely recyclable. This is a marked improvement over the more popular and far more compact lithium-ion batteries.

Deposits of vanadium are rare, but the mineral can often be found in other mineral deposits. It is commonly used to strengthen iron and steel.

“Vanadium is something for the future of energy storage.”

-Tahir Husain

Tahir Husain of Memorial University’s engineering department believes such batteries could be the future of energy grids, especially for renewable power sources.

“You have to find reliable renewable energy,” said Husain. “Most of the renewable energy is in the form of solar energy or wind energy. But they are for certain periods of the day and night, so you can not rely fully on that unless you find a way to store that energy somewhere. Vanadium is something for the future of energy storage.”

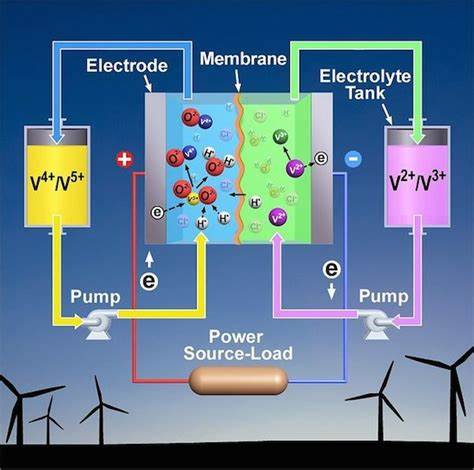

According to VanadiumCorp Resource Inc., the storage battery is made of two tanks of vanadium electrolyte solution, one positively charged and one negatively charged, with one or more “cell stacks” in between them.

The cell stack acts as an engine for the battery. The two solutions are pumped into each side while separated by an ion-selective membrane. During charging, the positive solution gives up an electron to the negatively charged half of the cell stack. When the battery is discharged to provide power, the opposite process takes place.

Husain thinks this versatile and scalable battery system would work perfectly as a “micro-grid” for Newfoundland and Labrador. Many of the provinces communities are far apart and sparsely populated and maintaining power infrastructure is costly. The technology would eliminate much of that infrastructure.

“There are 400-500 small communities scattered in the province,” said Husain. “They are very small, maybe sometimes 100 people in one community. And you cannot just connect them everywhere to the grid systems, it is not easy.”

“That’s not to say that in the future there won’t be a vanadium mine in Newfoundland, there’s a lot of potential for it, and Newfoundland and Labrador is under-explored”

– Gary Thompson

Gary Thompson, a geoscientist with the College of the North Atlantic, thinks that Newfoundland is a ways off from mining vanadium and using it for the production of batteries.

“There’s no [pure] vanadium deposits around … ready to be mined,” said Thompson. “That’s not to say that in the future there won’t be a vanadium mine in Newfoundland, there’s a lot of potential for it, and Newfoundland and Labrador is under-explored.”

“I feel that this place is very well suited for this purpose.”

– Tahir Husain

Husain isn’t deterred. Regardless of whether it’s mined here or elsewhere, he still thinks the technology could have a bright future in the province.

“A lot of oil processing, in Alberta for example, generates a lot of ash and it has a lot of vanadium in that,” said Husain. “You can extract vanadium from that and start moving in a direction to establish an industry.”

St. John’s could be a major shipping port for vanadium, he says, and a great place to process it.

“I feel that this place is very well suited for this purpose. Being a port city, for example, you can bring all kinds of these materials over here, process it and develop industry in that direction.”

Be the first to comment